The aura of excess returns has faded, the banking industry is “fighting back”, and the private equity boom is cooling down

The private equity business is losing its unique edge. Agencies like Ares Management (ARES.US) and Kuroishi (BX.US) have stolen deals from under the guise of giants such as JPM.US (JPM.US) and used their ability to provide customized terms to reap huge returns. The difference today is that the banking sector has made a strong recovery, while direct lenders are investing heavily in retail instruments, which provide investors with an opportunity to cash out. All in all, the $2 trillion private finance industry is becoming more and more like the public credit industry, which means declining returns.

In the few years after the outbreak of the pandemic, so-called direct lenders became kings in the field of leveraged finance. This is partly due to rival banking being hit hard by takeover loans (including Elon Musk's $44 billion Twitter takeover). This allows private equity funds to lend directly to borrowers while providing fast, definitive, and flexible terms, despite high interest rates. Direct lenders like Blackstone funded some of the biggest acquisitions at the time, such as the $10 billion acquisition of Zendesk in 2022. Meanwhile, rising interest rates have enabled these emerging institutions to promise double-digit returns to investors, which has attracted the attention of pension funds and insurance companies, thereby fueling this wave.

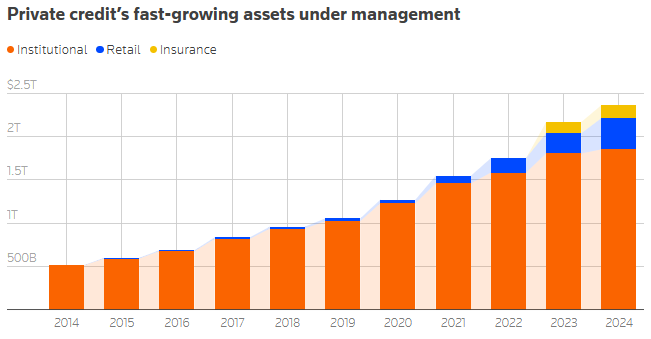

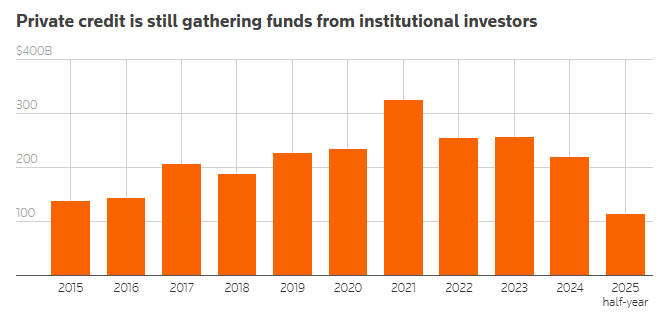

It is undeniable that the private equity giants have shown no sign of stopping their development. As of 2024, the asset size of the industry has grown steadily to $2.4 trillion. According to PitchBook data, in the first half of 2025 alone, traditional closed-end institutional funds raised $113 billion. Moreover, new sources of funding are increasingly complementing these traditional channels. So-called “perpetual funds” such as BCRED owned by Blackstone are growing rapidly. Such funds allow redemption within a certain limit, so they are popular among wealthy people. According to PitchBook estimates, in the six months up to the end of June 2025, these semi-liquid products raised $48 billion, or about 40% of the capital flowing into traditional institutional funds. And the hunt for retail funds will continue. After President Trump signed an executive order in August, fund managers may soon be able to attract funds from American retired savers. Consulting firm Oliver Wyman estimates that by 2029, the amount of personal wealth funds allocated to private equity credit could nearly quadruple to reach $1.5 trillion.

However, this huge scale of capital and evolving financing models have also raised new problems. It is difficult to find a suitable source for the funds raised. By the end of 2024, so-called “dry powder” (that is, uninvested capital) reached 543 billion US dollars. Banks that once contracted their front lines are now fighting back, driven by the boom in the credit market and the easing of US capital rules. The additional premium that investors need to pay to cover the risk of default on high-risk assets such as junk bonds fell to the lowest level after the crisis in 2025. Furthermore, sales of secured loan certificates (CLO, the instrument for banks to package loans) also reached record highs. According to LSEG data, this is one reason why leveraged buyout activity increased by nearly 17% in the nine months to the end of September, reaching 587 billion US dollars.

The hot debt market is putting pressure on the additional yield that direct lenders charge borrowers (higher than similar publicly issued bonds). This additional “premium” is a key selling point for such assets in the eyes of investors, and is historically usually about 2 percentage points higher than interest rates on similar bonds that are more widely traded. According to bankers in mid-November, this figure has been cut in half to just over 1 percentage point in Europe, and sometimes even lower in the US.

Furthermore, banks' leveraged finance departments are becoming more and more adept at structuring transactions to attract borrowers such as private equity firms. In Europe, for example, they are increasingly offering loans that can be drawn in installments, making it easier to finance multiple acquisitions. A recent example is Bain Capital's August investment financing plan for HSO, which is headquartered in the Netherlands, about $1 billion.

Private credit managers are also looking for new business growth points. Lenders like Blue Owl have become key players in financing artificial intelligence assets such as data centers. Apollo uses the strength of its Athene insurance division to provide customized financing to higher-rated companies. And institutions that focus on providing loans to small businesses can still avoid mainstream public bond or loan markets to obtain higher returns.

However, in the traditional field of acquisitions, private equity credit is gradually becoming a common financing tool. Borrowers are increasingly able to take advantage of the game between the market and lenders. Today, it is not uncommon for loans underwritten by direct lenders to be refunded in the loan and bond markets. According to PitchBook LCD data, in the first three quarters of 2025, the volume of such transactions was about $26 billion, which is roughly the same as the scale of reverse transactions. Moody's Investors Service notes that private lenders are increasingly willing to issue uncontracted loans, which further shows that competition for capital deployment is intense because these lenders will have control over troubled borrowers. This is in line with broader debt market trends.

As a result, if you take a step back, the line between private equity credit and traditional credit is becoming increasingly blurred, and traditional credit often means lower returns. The growth of retail funds has the potential to further narrow the gap between the two. Perpetual funds allow limited redemptions based on net asset value, which means they must regularly prove to financial advisors and regulators that the fund's valuation matches the actual situation. The corollary of this is that private equity loans will need to be traded more widely. A world with lower returns and greater liquidity is on the horizon, which will weaken what was once unique about private equity credit.

Index Options

Index Options State Street

State Street CME Group

CME Group Nasdaq

Nasdaq Cboe

Cboe TradingView

TradingView Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal