Govt’s DNB exit redraws risk map for telcos

THE government’s decision to exit Digital Nasional Bhd (DNB) marks a defining shift for Malaysia’s telecommunications sector, pushing the single wholesale network (SWN) for 5G from a policy-led project into one that must now withstand commercial and investor scrutiny.

Recall that DNB was created in 2021, with the Finance Ministry (MoF) as the sole shareholder.

Years later, four telecommunications companies (telcos) took stakes in DNB, with the MoF remaining the single largest shareholder.

What was once a state-led infrastructure project, largely insulated from commercial pressures, is today being pushed squarely into the hands of the country’s largest mobile operators.

With the MoF exercising its put option, CelcomDigi Bhd, Maxis Bhd and YTL Power International Bhd’s unlisted unit, YTL Communications Sdn Bhd, are required to collectively acquire the government’s remaining stake in DNB, each paying RM327.9mil.

Do note that U Mobile Sdn Bhd initially came into the picture as a wholesale customer and later became a shareholder of DNB under the SWN model, offering 5G services using DNB’s infrastructure.

Its role changed when Malaysia adopted a dual-network approach, with U Mobile selected to build the second 5G network, leading it to exit DNB’s shareholding to focus on rolling out its own network.

Upon completion of the transaction, CelcomDigi, Maxis and YTL Communications will each own a one-third stake and assume full responsibility for a national 5G network that has yet to reach financial sustainability.

The shift may appear administrative on the surface, but for investors and analysts, it fundamentally alters how risk is distributed, priced and ultimately absorbed within Malaysia’s telecommunications sector.

The implications extend well beyond a one-off cash outlay.

Earnings visibility, dividend durability, balance-sheet flexibility and, perhaps most importantly, the long-held perception of telcos as defensive yield stocks are now being reassessed.

Under government stewardship, DNB operated under a different set of incentives.

Losses were tolerated in pursuit of national coverage targets, while commercial discipline was secondary to policy objectives.

Funding gaps were bridged through shareholder advances, guarantees and regulatory support.

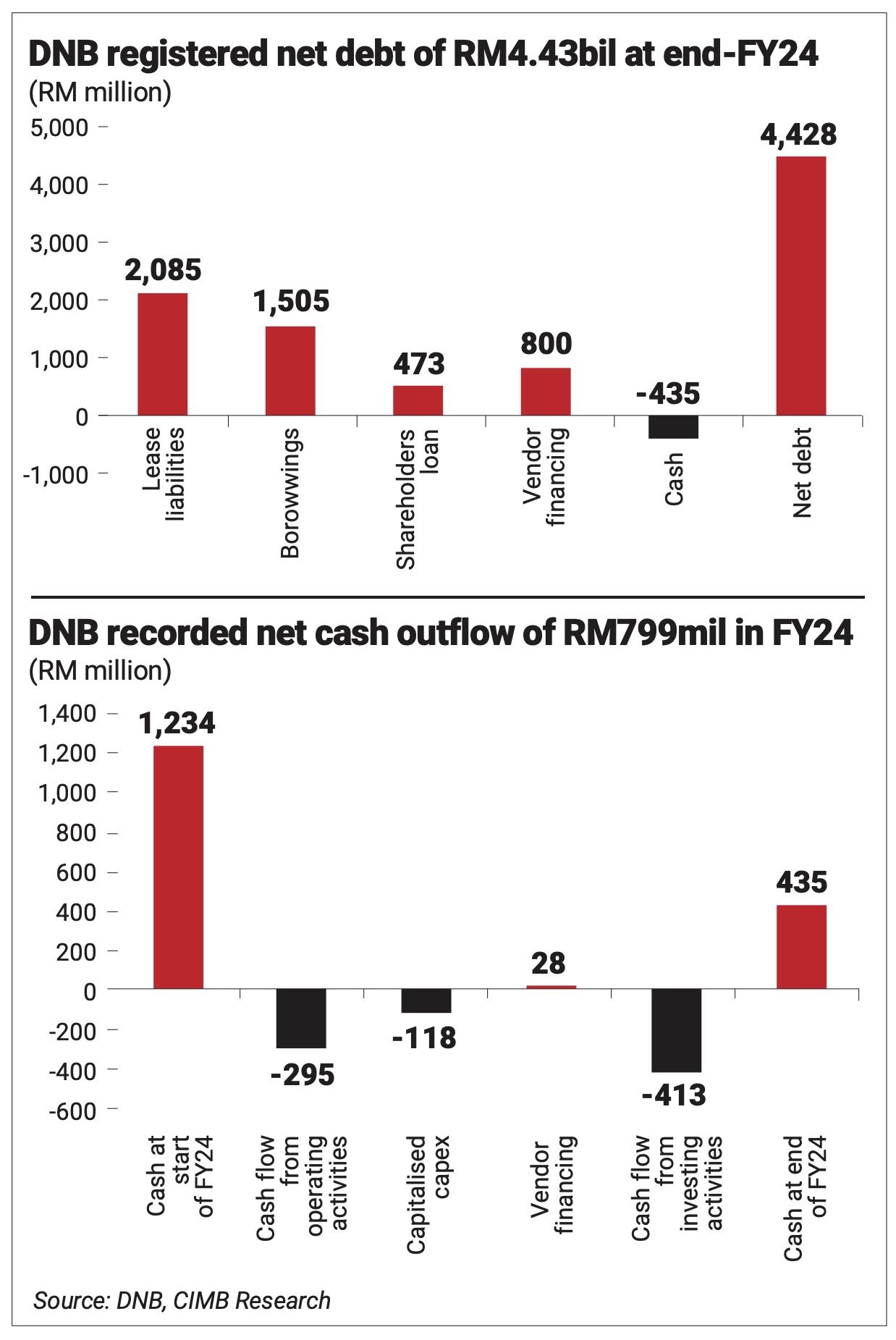

For financial year 2024 (FY24), DNB recorded a net loss of RM1.21bil on revenue of just RM341mil, reflecting low utilisation, constrained revenue recognition and a cost structure built for scale that has yet to fully materialise.

Network operating costs, financing expenses and depreciation continued to run ahead of wholesale revenue, as 5G adoption remained gradual and pricing considerations remained sensitive.

As at end-FY24, DNB’s net debt stood at RM4.43bil, while accumulated retained losses exceeded RM3.1bil – a balance sheet that would be untenable for most standalone operators.

Until now, those concerns were softened by the implicit backing of the state.

Once the government exits, however, CelcomDigi, Maxis and YTL Power will need to account for a bigger share of the losses.

However, the immediate earnings setback, while uncomfortable, is not disastrous.

Khair Mirza, head of airport investor resource and industry research at Canadian transport infrastructure consultancy Modalis Infrastructure Partners, views the impact in relative terms.

“A RM300mil annual loss would be as little as less than 5.5% of CelcomDigi’s 12-month run-rate reported earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation, or as much as 6.9% for Maxis,” he tells StarBiz 7.

In other words, the drag is visible but manageable.

The more pressing concern is not whether the telcos can absorb the losses, but how long those losses will persist and what second-order effects they may trigger.

EPS dilution material but not terminalFor equity investors, the headline risk lies in earnings per share (EPS) dilution.

Based on consensus assumptions that DNB continues to post annual losses of around RM300mil, the impact could be meaningful.

“From a purely financial perspective, EPS dilution could be as much as 19% if DNB turns an annual RM300mil loss,” Khair says.

This could represent a significant impact, particularly for income-orientated investors accustomed to stable earnings and predictable dividends.

While the losses are largely non-cash in nature, equity accounting still depresses reported profits, which in turn affects valuation multiples and payout ratios.

However, analysts caution against extrapolating worst-case dilution over the long term.

Several mitigating factors are already in motion, including higher minimum commitment fees, revised access agreements, spectrum reassignment and the potential for cost rationalisation under private management.

CIMB Research estimates that with reduced staff costs, lower licence fees and softer financing terms – especially if government support continues in the form of concessional loans – DNB’s annual cash cost could be reduced to around RM1.1bil by FY26, from RM1.3bil in FY24.

While still elevated, this narrows the gap that wholesale revenues need to bridge.

Dividends not derailed

The more emotive question for investors is whether dividends are now at risk.

At first glance, the combination of a RM327.9mil cash outflow and recurring equity losses appears detrimental to payouts.

But most analysts stop short of forecasting outright dividend cuts. On whether dividends are at risk, Khair says, “On a ‘business-as-usual’ basis, yes, it would seem so.”

He quickly adds a crucial counterbalance: “We could expect, however, that the government would be sympathetic to any regulatory concerns the new joint-managing shareholders would have, so as to optimise the value of the DNB network, and thus minimise the impact to dividends eventually.”

This nuance is important. While the government may be exiting as a shareholder, it remains deeply invested as a policymaker.

Ensuring that national champions remain financially healthy and investible is not a trivial consideration, particularly as Malaysia seeks to attract long-term capital.

An industry expert reinforces this view, arguing that dividend outcomes will hinge less on DNB losses per se and more on how the telcos allocate capital across successive generations of technology.

“If they spend on DNB’s network, they potentially reduce investments in 4G. Same pattern with past tech upgrades – 2G to 3G to 4G,” he tells StarBiz 7.

In other words, dividends are unlikely to be the first casualty, as capital expenditure (capex) priorities are more likely to be adjusted first.

Two networks with one capital pool

Beyond earnings and dividends lies a more structural challenge: how telcos balance investments in DNB while continuing to maintain and upgrade their own networks.

Under the SWN model, DNB was intended to reduce duplication and free up capital.

In reality, operators have continued to maintain parallel 4G networks and supporting infrastructure, limiting the capex relief originally envisioned.

“Ideally, the new managing shareholders would already have a fair view of balancing investing into their own individual networks with any required investments into DNB’s network, to extract an optimum outcome from DNB,” Khair says.

This balancing act becomes more complex if DNB requires further capital injections.

Beyond the RM327.9mil buyout, the question of additional funding looms.

“This might be too early to tell, subject potentially to new management that would be able to execute in line with the new managing shareholders’ expectations,” Khair notes.

The industry expert is less equivocal, saying additional top-ups are “likely depending on the scale of network expansion”, though he adds that DNB’s new ownership structure should make debt funding easier and cheaper.

Despite these uncertainties, balance-sheet stress at the telco level appears contained.

TA Research points out that both CelcomDigi and Maxis can fund the buyout using internal resources, supported by cash balances of RM663mil and RM899mil, respectively, as at the third quarter of FY25.

Joint ownership also diffuses risk.

“The joint ownership of the three new shareholders should position it optimally to meet the detailed needs of the country’s top three leading mobile telcos,” Khair says.

That said, rating agencies will be watching closely. On the risk of downgrades, Khair concedes: “Yes, though under new ownership, it would be a surprise if the size of (DNB’s) annual losses continues.”

In effect, the market is giving management the benefit of the doubt – but not indefinitely.

Efficiency gains and utilisation pressure

A constructive argument is that higher utilisation of DNB’s network will unlock cost efficiencies, as network costs are largely fixed.

Khair is unequivocal on the consequences of failure: “Any failure to efficiently shift peak loads would be an indictment of the original network design and could, in fact, potentially justify the takeover of the network and licence by commercial parties.”

The industry expert concurs. “With any network, the more you carry the lower the unit cost. Costs are fixed, not variable.”

The reassignment of an additional 100 megahertz (MHz) of contiguous spectrum to DNB strengthens this narrative.

With 200MHz now operating across the 3.3 to 3.5GHz band, DNB has regained capacity that was previously compromised by the shift to a dual-network model, without requiring incremental capex, according to management.

This additional spectrum is critical not only for consumer traffic but also for enterprise and industrial 5G use cases, which are widely expected to drive the next phase of monetisation.

If utilisation is key, then U Mobile’s rollout of a second 5G network becomes a strategic wildcard.

“Yes, it could in theory,” Khair says when asked whether U Mobile’s expansion could reduce DNB utilisation and worsen earnings drag.

“An external observer would still wonder why a second, competing network exists.”

The industry expert is more direct, flagging 2027 to 2028 as the inflection period when U Mobile’s traffic migration could materially affect DNB, particularly if pricing discipline breaks down.

U Mobile, however, remains publicly aligned with policy.

“We are not in a position to comment on the matter as we are not a shareholder of DNB.

“However, U Mobile is committed to implementing the dual 5G network strategy as per the government’s directive,” chief executive officer Wong Heang Tuck tells StarBiz 7.

The coexistence of two networks raises unresolved questions around scale, duplication and long-term economics.

One fear among investors is that heavier reliance on DNB could reduce telcos’ ability to differentiate on network performance.

Khair dismisses this concern.

“No, main differences are mainly calculated in customer service, last-mile latency and account management.

“These aren’t ordinarily differentiated at the backbone infrastructure network level.”

The industry expert goes further, challenging the premise altogether.

“Why should network quality be a differentiator? Should the network not be a utility?”

If that view prevails, DNB’s role as a shared backbone may ultimately support, rather than undermine, industry economics – provided governance and pricing remain aligned.

Valuations and policy discount

Ironically, many analysts argue that the biggest drag on valuations is not the DNB transaction itself, but lingering policy uncertainty.

“The uncertainty of policy and heavy-handed federal government direction would weigh more on sector valuations than an inelegant, one-off transaction,” Khair says.

The episode has reopened a fundamental question that extends beyond DNB: is spectrum perpetual?

Until investors have clarity on spectrum tenure, renewal terms and regulatory consistency, Malaysian telcos are likely to trade at a discount to regional peers, regardless of operational performance.

In the immediate term, absorbing DNB does weaken the sector’s defensive investment appeal.

Earnings volatility rises, policy risk remains elevated and valuation multiples may remain compressed. Khair acknowledges this.

“In the immediate term, yes.”

But he also frames the outcome as inevitable, and potentially constructive, over the long run.

“In the long-term, it would have probably been a requirement, so as to optimise utilisation and synergies for the operators themselves.”

In that sense, the government’s exit forces a reckoning.

The 5G experiment now shifts decisively from policy ambition to commercial execution.

For investors, the narrative moves from “Will the government step in?” to a more demanding question: can management make this work?

That transition may be uncomfortable. But if executed well, it could ultimately lay the foundation for a more rational, investible telco sector in the years ahead.

Index Options

Index Options State Street

State Street CME Group

CME Group Nasdaq

Nasdaq Cboe

Cboe TradingView

TradingView Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal