British Treasury bonds are about to come: stabilizing buyers' exits, short-term capital dominates market fluctuations

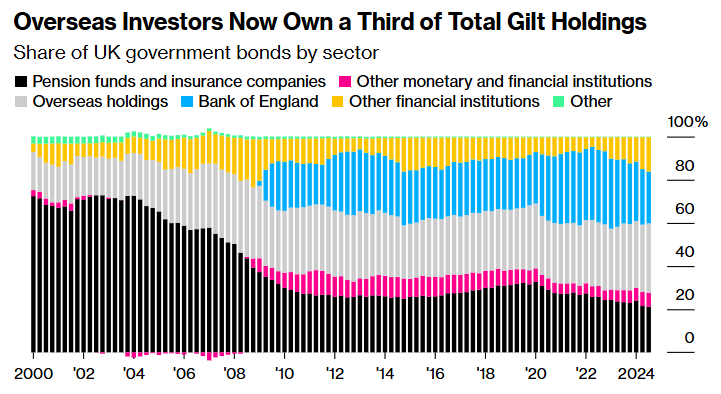

The Zhitong Finance App learned that the pattern of the British bond market is changing, making British treasury bonds a weak link in the current time when the government needs to maintain a stable situation the most. This week alone, the Bank of England and financial regulators both issued warnings, saying that this change in the demand structure poses a potential risk and may cause bond prices to fluctuate more drastically, or even a wave of sell-offs. The message is clear: markets that were once dominated by steady buyers (such as pension funds and the Bank of England) are now extremely vulnerable to volatile players (such as hedge funds and foreign investors), making them extremely vulnerable.

For British Prime Minister Keir Stammer and Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves, the problem is that when this transformation occurred, they directly linked the government's economic policy to the trend of British Treasury yields, and they were already implementing policies close to the limits of their own fiscal rules.

This makes their entire plan entirely dependent on an unpredictable market and more focused on any changes in fiscal policy. Many erratic measures have not had a positive effect, but the reason why the rapid fluctuation in investor sentiment caused by these changes is that the investor community itself has fundamentally changed.

Liam O'Donnell, fund manager at Artemis Investment Management, said: “The UK is facing the biggest shift in structural supply and demand relationships on a global scale. If I look back at the biggest buyers of British Treasury bonds in the past 10 to 15 years, two of them are no longer participating in market transactions.”

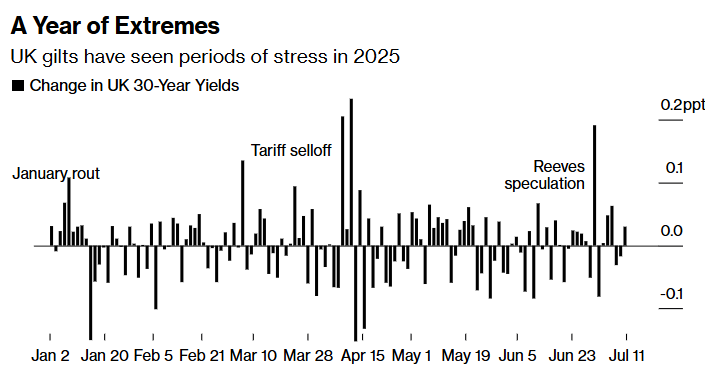

In the years following the sharp drop in UK treasury bonds that led to the collapse of the Leeds Truss administration in 2022, these securities were vulnerable to any sign of fiscal overspending. The most recent example was last week, when rumors about a new Chancellor of the Exchequer triggered a sharp rise in yields.

But even if the problem does not stem from the UK itself, the British market will be hit hard, which indicates that there is a deeper problem.

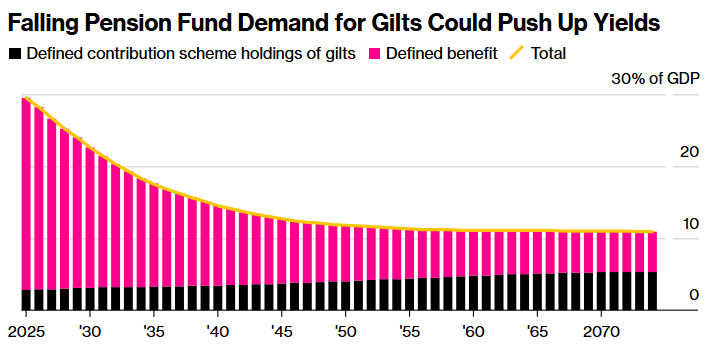

For decades, the UK has been able to meet its debt repayment needs by purchasing fixed-income pension funds with almost unlimited demand. These funds hope to match the size of their debt by investing in long-term treasury bonds. At the same time, however, these purchases are gradually declining, and at the same time, the Bank of England (which has accumulated nearly 1 trillion pounds (about 1.4 trillion US dollars) of treasury bonds through its quantitative easing program) has been reducing its treasury holdings, thereby increasing the supply of bonds, as the government is also seeking more borrowing.

The huge supply combined with the departure of two major buyers meant that others needed to fill the gap. Funds with global investment strategies are getting involved, but as the UK market has plummeted in recent years due to the Brexit to Atlas treasury debt crisis, the willingness to buy these funds depends more on price. “The UK needs to attract foreign investment, but given the current political chaos, I don't think this dependency is reliable,” O'Donnell said.

Although these situations are not unique to the UK, in many ways the UK is leading the way in changing the global bond market structure. The UK is currently in a particularly difficult situation due to the fiscal rules set by the government itself. Reeves set aside only £10 billion in buffer funds in the March financial report to address these budget red lines. Since then, due to a reversal in spending reduction policies, slow economic growth, reduced tax revenue, and higher spending requirements, the UK treasury is currently in deficit, and the size of the deficit could reach several billion pounds.

This makes changes in UK Treasury yields (this indicator is an important factor to consider in fiscal rules because it reflects the government's borrowing costs) extremely important. In particular, the yield on longer-term bonds remains high. This unstable fiscal calculation has led to the government's many embarrassing policy reversals.

Bloomberg macro strategist Ven Ram said, “The UK is facing a dilemma where tax revenue is falling without a corresponding reduction in spending. At the same time, economic growth is also below pre-pandemic levels. This will result in a rise in debt as a share of GDP. In addition, the £5 billion welfare spending cuts that have now been cancelled have increased fiscal pressure, and investors should be demanding higher real risk premiums and inflation risk premiums to hold longer-term treasury bonds.”

What worries policy makers is that treasury yields seem prone to sudden sharp increases. In the fall, a rapid sharp rise caused Reeves' first budget plan to lose public attention. Then in January, the cost of a 30-year loan reached its highest level since 1998, which brought more unwelcome negative news about the government and paved the way for fiscal austerity policies in March. Market turmoil caused by Donald Trump's tariff statement in April also dealt a heavy blow to treasury bonds, further boosting yields.

James Athey, fund manager at Marlborough Investment Management, said, “Insufficient liquidity and unbalanced position structures mean that the magnitude of price fluctuations far exceeds the extent of impact that should have been felt in the news. The root cause is the huge supply of British treasury bonds and the government's 'terrible fiscal calculations'.”

Britain's financial watchdog, the Office of Budget Responsibility, warned on Tuesday that the government is becoming increasingly vulnerable to foreign investors due to falling demand for pensions. A model from the agency suggests the change could increase interest rates on government debt by 0.8 percentage points.

Some investors also point out that the rise of hedge fund strategies has led to increased market volatility. In the first five months of 2025, their activity in UK treasury bonds trading on the Tradeweb platform accounted for 59% of the total trading volume. This percentage is higher than peers in Europe and the US, and is up from 44% in 2020.

The Bank of England also expressed similar concerns on Wednesday, warning that a quick liquidation of its trades would pose a threat to financial stability. Bank of England Governor Bailey pointed out that last week's move is the latest example of “the current market is more volatile.”

Index Options

Index Options State Street

State Street CME Group

CME Group Nasdaq

Nasdaq Cboe

Cboe TradingView

TradingView Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal