What Is a Short Put?

Introduction

You believe that the stock you have been researching may experience higher price movement during a given time frame regardless of general market conditions, and you would like to generate some income in the near term. You are familiar with long stock positions but are wondering if there is a less capital-intensive method to express this investment hypothesis through a trade.

Options, a type of derivatives contract, are one possible solution for efficiently gaining exposure to stock performance. They are classified as derivatives because the value of the options contract is “derived” or based on the price of something else (in this case, a stock). Remember that with all choices there are risks and benefits that we need to fully understand. This allows us to make informed decisions before using products to express investment opinions.

Put options give the holder the right, but not obligation, to sell a security (like a stock) at a predetermined price known as the strike price on a future date in time. Let’s explore this building block of financial choice in greater detail together.

Fun fact: Why is it called a “put”? Quite simply because the purchaser of a put option has the right to “put up for sale” the stock or underlying.

What is a Short Put?

First, let’s learn options contract language to understand the details for when we sell, or are “short,” a put option. Each standardized listed options contract has specifications that set the terms of the agreement between the buyer and the seller:

- Quantity – The number of contracts you are purchasing

- Underlying – The security (stock, index, etc.) that the option’s value is derived from

- Expiration – The specific date and time an options contract expires

- Strike Price – The price at which an option can be exercised or assigned (or converted to the underlying)

- Type – Call or Put

- Price – The price that the option is bought (or sold) for

- Style – American (can exercise your right on or before expiration) or European (can only exercise your right on expiration)

- Settlement Style – Physical (the underlying security is delivered) or Cash

- Contract Multiplier – The number of underlying shares or units represented by one contract; for our examples we will assume a 100 multiplier, meaning each contract represents 100 shares or units of the underlying

With that in mind, we can now explore what it means to sell a put or have a short put position. A short put is the obligation to purchase stock at the strike price on a future date in time.

Let’s focus on the difference between long puts (buying puts) and short puts (selling puts) to reinforce the contractual difference. The put buyer controls the decision to exercise the right to sell the underlying at the strike price, not the put seller. When a put buyer exercises the right, the seller is assigned, or obligated, to buy stock at the strike price.

When you sell put options contracts, you collect money to establish the position. Let’s refer to this as the premium collected. The net premium collected also includes the offsetting costs of fees.

As a strategy, the short put is considered a “single-leg” strategy because it utilizes only one options contract. As we build on our understanding, we will explore two-leg and multi-leg strategies as well.

Selling put options, by design, is a capital-efficient way to express a bullish opinion on a stock or the market; we anticipate value increasing and price rising. The trade-off for generating income or collecting money with the short put is the significant, but capped, downside loss potential of the position. Because of this risk exposure in the short put strategy, additional account permissions are required.

Example

Sell 10 XYZ January 50 puts for $1.63

Assume the current XYZ stock price is $50

- Quantity – 10 contracts

- Underlying – XYZ stock

- Expiration – January

- Strike Price – 50

- Type – Put

- Price – $1.63 per contract

- Style – American

- Settlement Style – Physical shares

- Contract Multiplier – 100

How do we generate income on our bullish stock opinion with the embedded risk obligation to buy 1000 shares of XYZ stock for $50 in January, if assigned?

(Note: Total shares represented = quantity of options contracts x options contract multiplier = 10 x 100 = 1000)

We first complete our transaction by collecting $1,630 less fees and commissions. The transaction itself generates income for your account while obligating you to buy stock at $50, the strike price, in January if you are assigned to do so. The assignment risk increases as the price of the stock declines toward $50 and assignment is highly likely once the stock price declines below $50.

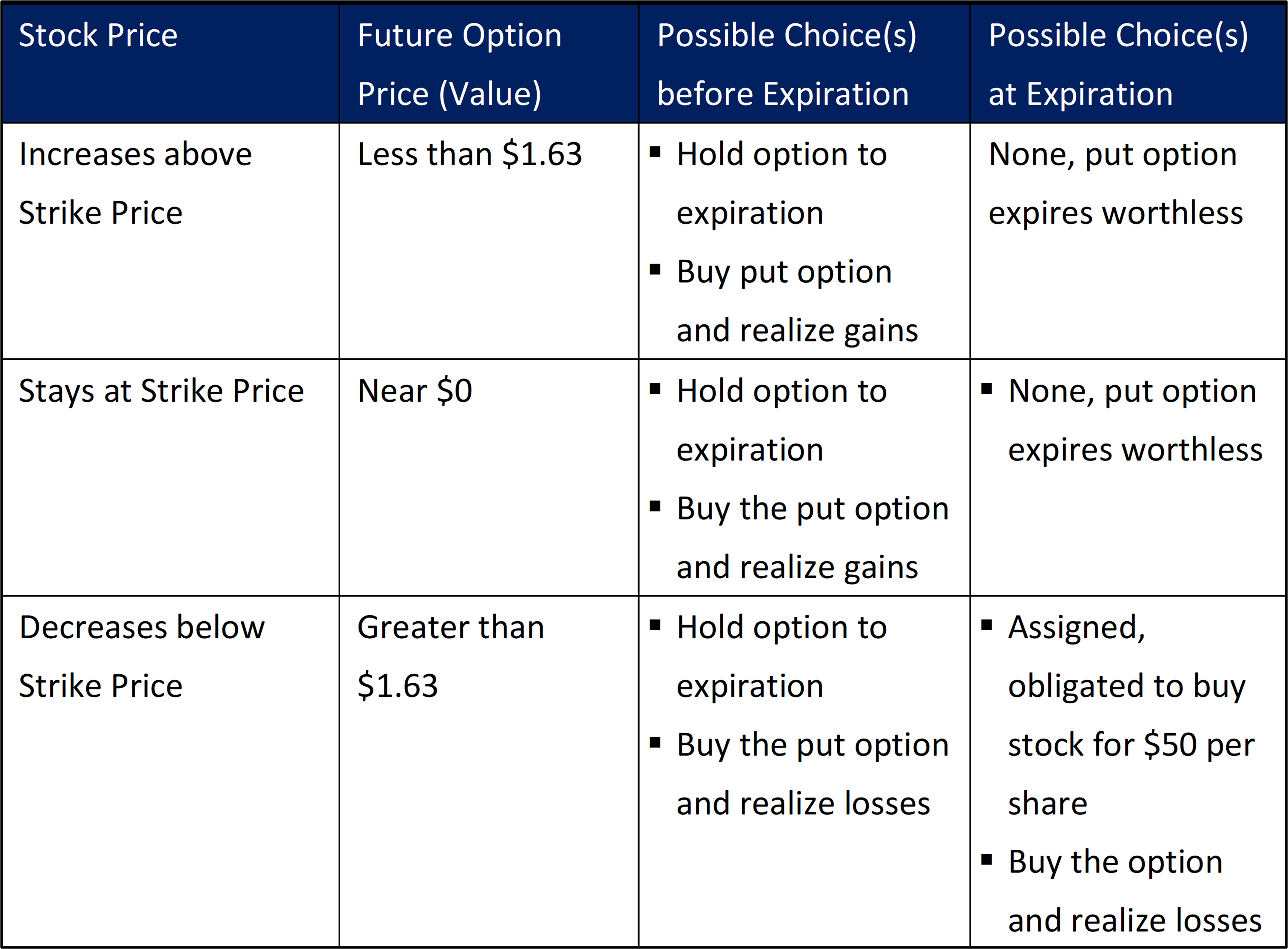

Before we complete the transaction to sell puts, let’s look a bit further at the decisions we face before and on the contract’s expiration date:

-Powered by The Options Institute

Index Options

Index Options State Street

State Street CME Group

CME Group Nasdaq

Nasdaq Cboe

Cboe TradingView

TradingView Wall Street Journal

Wall Street Journal